Till now we have been told that the history of early civilizations begins with Mesopotamia, between 4000-3500 B.C., which was considered the cradle of civilization. Located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq, Kuwait, and Syria, Mesopotamia saw the development of urban cities such as Babylon, Ashur, and Akkad.

Following Mesopotamia, around 3100 B.C., ancient Egypt rose to prominence along the Nile River. Known for its monumental pyramids, tombs, and mausoleums.

Concurrently, the Indus River Valley Civilization, emerging around 3300 B.C. in modern-day India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, was characterized by its organized city planning, featuring baked-brick homes, a grid structure, and advanced water management systems.

Unlike other ancient civilizations, it did not appear to experience frequent warfare. In China, beginning around 2000 B.C., early civilizations developed in relative isolation due to natural barriers like the Himalayan Mountains, the Pacific Ocean, and the Gobi Desert.

The Chinese built early fortifications against northern invaders, precursors to the later Great Wall of China. Meanwhile, in ancient Peru, around 1200 B.C., various cultures, including the Chavín, Paracas, Nazca, Huari, Moche, and Inca, thrived, demonstrating expertise in metallurgy, ceramics, and advanced medical and agricultural practices.

In Mesoamerica, also beginning around 1200 B.C., the region saw the rise of the Olmec civilization, followed by the Zapotec, Maya, Toltec, and eventually the Aztecs, all of which shaped the cultural and historical landscape of today’s Mexico and Central America.

Discovering the Mother of All Civilizations: The Harappan Civilization (Indus Valley)

The Harappan Civilization, recognized as the earliest complex society in ancient South Asia, has been a source of fascination for historians and archaeologists alike. Despite significant efforts to explore its cities and urban centers, much remains unknown about its burial practices.

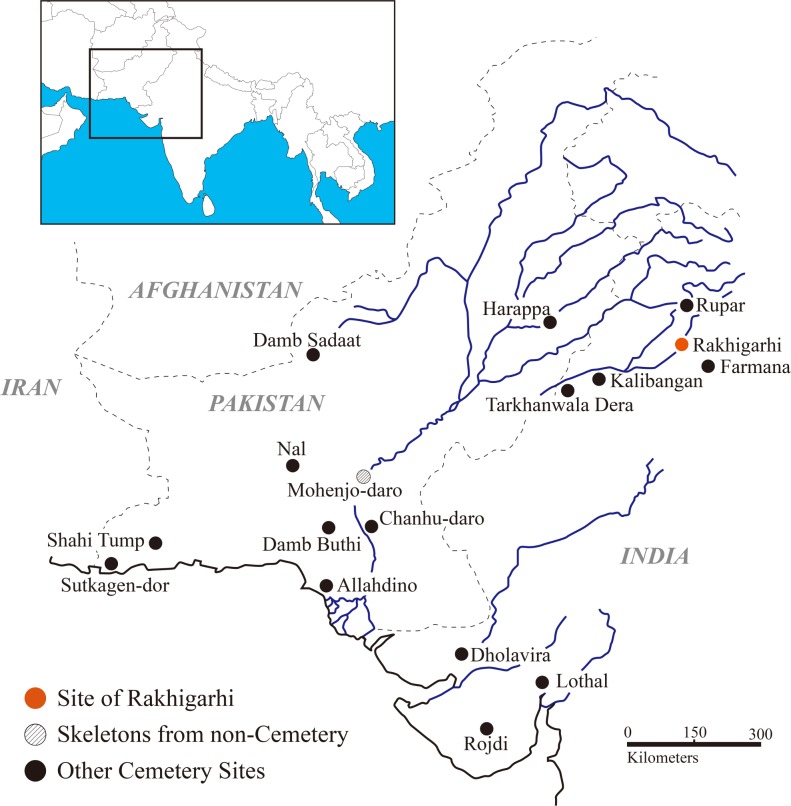

Notably, an insufficient number of archaeological surveys have been carried out on Harappan cemeteries, leaving a considerable gap in our understanding of how these people treated their dead. One such site that has drawn recent attention is Rakhigarhi, located in Haryana, India—one of the largest cities of the Harappan Civilization.

The Rakhigarhi Necropolis: New Insights

From 2013 to 2016, excavations were conducted at the necropolis in Rakhigarhi to address the lack of archaeological data. The findings from these excavations offer significant new insights into Harappan mortuary practices. Different types of graves were identified, with primary interment being the most common, followed by secondary burials, symbolic graves, and unused (empty) graves.

Among the primary burials, several atypical interments stood out, suggesting elaborate preparation for the deceased. Of particular interest were prone-positioned burials, which have traditionally been interpreted as a marker of social deviance.

However, the findings at Rakhigarhi challenge this notion, indicating that these individuals may not have been deviants, prompting a reassessment of such interpretations within Harappan archaeology. The Rakhigarhi excavations reveal a variety of burial types that reflect the diverse mortuary rituals practiced by the Harappan people.

This diversity provides a glimpse into the ways in which the Harappan society honored their dead, suggesting a complexity in their burial customs that had not previously been fully appreciated.

The Historical Significance of Harappan Civilization

The Harappan Civilization, also known as the Indus Valley Civilization, dates back to 5500 BCE, according to recent excavations in the Ghaggar Basin (also known as the RigVedic Saraswati region). Spanning southeastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern and western India, the Harappan Civilization was remarkable for its advanced urban planning, metallurgical techniques, and standardized measurement systems.

Five major urban centers—Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Ganweriwala, Rakhigarhi, and Dholavira—served as hubs of political and economic activity, surrounded by smaller settlements.

Archaeological research has demonstrated that the Harappan people were highly sophisticated, with extensive trade networks and shared cultural traditions across their region. Their cities were well-planned, featuring organized drainage systems, roads, and public infrastructure. However, while much attention has been given to these urban centers, relatively little is known about the Harappan cemeteries.

This oversight is partly due to the remote locations of burial sites, as well as natural erosion that has obscured the original features of the burial mounds.

Previous Cemetery Excavations

Over the past century, archaeologists have uncovered several Harappan cemetery sites, including those at Harappa, Kalibangan, Farmana, Rakhigarhi, and Sanauli. However, the data collected from these sites has been limited, leaving researchers with an incomplete picture of Harappan burial practices.

Many cemeteries have remained unexplored, and the existing excavations have not yet provided a comprehensive understanding of how the Harappan people treated their dead.

Nonetheless, interdisciplinary studies have yielded valuable insights into the lives and practices of the Harappan people. For example, isotopic analyses have shed light on individual migration patterns, linking city populations to rural communities.

Similarly, dietary and pathological studies have provided information on the health and lifestyles of the Harappan population, while paleopathological research has revealed details about their physical conditions, including evidence of cranial trauma and leprosy.

The Rakhigarhi Excavations (2013-2016)

The excavations conducted at Rakhigarhi from 2013 to 2016 represent an important step forward in the study of Harappan burial customs. Over three consecutive excavation seasons, researchers uncovered significant details about the necropolis, offering new perspectives on how the Harappan people were buried.

The discoveries of various grave types, including prone-positioned burials and symbolic graves, contribute to a growing understanding of the complexity of Harappan mortuary practices.

These findings are particularly significant because Rakhigarhi was one of the largest cities of the Harappan Civilization and served as a major political and economic center. Despite its importance, previous archaeological surveys had left much of the cemetery untouched.

The recent excavations have begun to fill this gap, providing a clearer picture of how the people of Rakhigarhi buried their dead and the social and cultural significance of their burial practices.

The discovery of diverse burial types and the presence of elaborately prepared graves suggest that Harappan mortuary rituals were more varied and complex than previously thought. While much remains to be uncovered, these findings contribute to our growing understanding of Harappan society and its respect for the dead.

As future excavations continue, the secrets of Harappan cemeteries may yet provide further insights into the lives and beliefs of this ancient civilization.

References