The Kakawin Ramayana, dating back to the 9th century AD, stands as a testament to Indonesia’s rich cultural heritage. As arguably the oldest Old Javanese epic text composed in Indic metres, this masterpiece has not only endured the test of time but has also profoundly influenced various forms of artistic expression. From the majestic reliefs of Central Javanese temples to modern puppet-show performances, the Kakawin Ramayana has left an indelible mark on Indonesia’s literary and cultural landscape.

Historical Roots and Cultural Fusion

The Kakawin Ramayana is a remarkable re-elaboration of the great Ramayana, originally ascribed to Valmiki in the 6th–1st century BC. What sets this Old Javanese poem apart is its unique blend of Sanskritic tradition with indigenous Javanese elements. This intricate fusion not only documents cultural interactions but also showcases the cultural creativity and craftsmanship of the Javanese people.

Composition and Sanskrit Prototype

The poem, written in Kawi, an old Javanese language, boasts a virtuoso array of metrical patterns. Unlike many Old Javanese texts, the Kakawin Ramayana has a specific Sanskrit prototype identified as the Bhattikavya, a challenging poem dating back to the 7th century AD.

This Sanskrit precursor, itself a version of Valmiki’s Ramayana, serves as the foundation upon which the Old Javanese poem skillfully builds, creating a unique narrative enriched with local cultural nuances.

Local Elements and Wayang Kulit Tradition

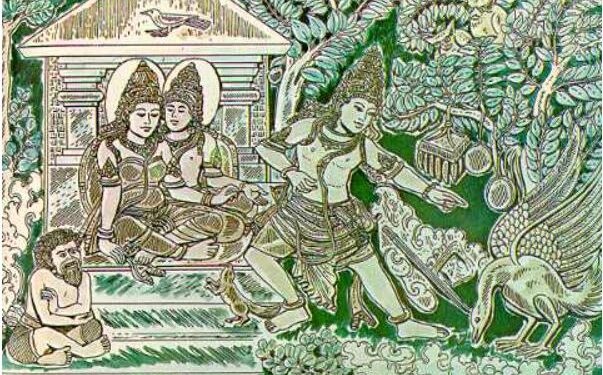

The Kakawin Ramayana is not a mere translation of Valmiki’s story. It introduces local Javanese cultural elements and seamlessly incorporates traditions of wayang kulit, a traditional Javanese shadow puppetry. One notable modification is the inclusion of the indigenous Javanese guardian demigod, Semar, and his sons, Gareng, Petruk, and Bagong, collectively known as the Punokawan or “clown servants.” These additions contribute to the distinctiveness of the Javanese version.

Geographical Impact: Bali and Beyond

The influence of Kakawin Ramayana extends beyond Java, reaching the neighboring island of Bali. Here, it further evolves into the Balinese Ramakavaca, enriching the cultural diversity of Indonesia.

Bas-reliefs depicting Ramayana and Krishnayana scenes adorn the 9th-century Prambanan temple in Yogyakarta and the 14th-century Penataran temple in East Java, emphasizing the widespread impact of the epic.

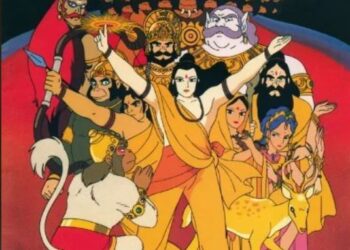

The Balinese kecak dance, for instance, narrates the Ramayana story through the roles played by dancers embodying Rama, Sita, Hanuman, and others, accompanied by a chorus of chanting men. Similarly, the Wayang Wong Javanese dance in Yogyakarta and the Ramayana Ballet at the Trimurti Prambanan open-air stage showcase the enduring influence of Kakawin Ramayana in diverse artistic performances.

Cultural Significance and Adaptations

In Indonesia, the Ramayana has become deeply ingrained in the culture, particularly among the Javanese, Balinese, and Sundanese people. Serving as a source of moral and spiritual guidance, as well as aesthetic expression and entertainment, the Kakawin Ramayana has inspired various art forms such as wayang and traditional dances.

Conclusion

The Kakawin Ramayana, with its roots in the 9th century, holds a special place in Indonesia’s literary and artistic legacy. Its intricate blend of Sanskritic tradition and local Javanese elements, coupled with its enduring impact on various cultural expressions, attests to the resilience and creativity of Indonesia’s cultural heritage. As the Javanese consider it the pinnacle of artistic expression, the Kakawin Ramayana remains a revered and influential text, preserving the essence of an ancient epic in the vibrant tapestry of Indonesian culture.