The Ramayana, an epic Sanskrit poem narrating the life and journey of Lord Rama, transcends geographical boundaries and cultural diversities. Its influence extends far beyond India, reaching the shores of Japan where it has woven itself into the fabric of the nation’s artistic expressions and spiritual beliefs. Let’s embark on a fascinating journey to explore how Ramayana exists in Japan.

Historical Significance: A Journey Through Time

The Ramayana’s journey to Japan began around the 8th century, carried by Buddhist monks and traders along the Silk Road. Early references appear in texts like the “Hobutsushu” (Jewel Collection), a 10th-century collection of Buddhist tales, and the “Sambo Ekotoba” (Illustrations of the Three Jewels), a 12th-century pictorial representation of Buddhist teachings. These texts adapted the tale, incorporating Buddhist elements and local deities.

By the 10th and 12th centuries, the Ramayana gained greater prominence through artistic mediums like Kabuki, a traditional Japanese theatrical form. Plays like “Yoritomo Nikki” and “Shuten Dōji” drew inspiration from the epic, portraying themes of good versus evil, filial piety, and righteous leadership.

From Pages to Screens: An Animated Rendition

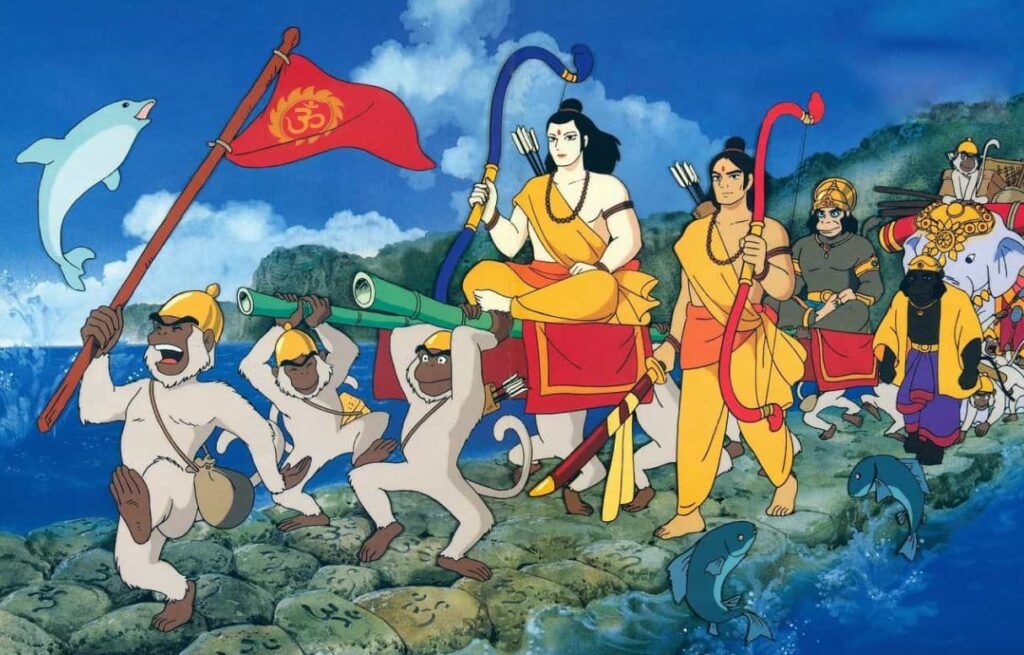

In the 1980s, the Ramayana truly captured the hearts of Japanese audiences with the release of the anime series “Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama”. This stunningly animated adaptation, directed by Yugo Sako, captured the essence of the original story while incorporating Japanese sensibilities.

So smitten by the story of Shri Ram’s triumph over the forces of darkness, that Japanese producer and director Yugo Sako read Valmiki’s Ramayana in Japanese and went on to study ten different versions before crafting this award-winning masterpiece. The series became a phenomenal success, winning awards and introducing a new generation to the epic tale.

Similarities and Differences: A Comparative Look

While the core narrative of Rama’s battle against Ravana remains constant, the Japanese Ramayana exhibits fascinating differences. Characters like Hanuman, the mighty vanara warrior, are often depicted as monkey gods, reflecting the Shinto deity Son Wukong. Sita’s abduction is sometimes attributed to a jealous goddess, adding a unique twist to the story.

The endings also diverge. Unlike the joyful return to Ayodhya in Valmiki’s Ramayana, the Japanese versions often conclude with Rama and Sita ascending to heaven, emphasizing their divine nature. These variations reveal the creative adaptation of the Ramayana to suit the Japanese cultural context.

Beyond Stories: Integration into Japanese Culture

The Ramayana’s influence extends beyond mere storytelling. Several Hindu deities have been absorbed into the Japanese pantheon, albeit with altered names and attributes. Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge and music, is worshipped as Benzaiten. Kichijoten embodies Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. These shared deities serve as a bridge between the two cultures.

Furthermore, the themes of duty, honor, and self-sacrifice resonate deeply with the Japanese ethos. Bushido, the code of the samurai, finds parallels in the Ramayana’s emphasis on dharma (righteousness). This shared value system further strengthens the connection between the two cultures.

Echoes of the Dharma: Ramayana’s Timeless Wisdom

The Ramayana’s journey in Japan is a testament to the power of storytelling to transcend borders and cultures. It speaks to our shared humanity, the universal values of good versus evil, and the enduring strength of the human spirit. As we navigate the complexities of our own world, may the timeless wisdom of the Ramayana continue to guide us, reminding us that even in the darkest of times, light will always prevail.